Abstract

Keeping cats indoors protects them from cars, disease, and wildlife—but the science is now brutally clear: physical safety alone is not enough. Indoor cats with poor enrichment are more likely to develop obesity, stress-related disease, and behavior problems such as inappropriate elimination and overgrooming.

This whitepaper synthesizes current guidelines from Cornell, AVMA, VCA, and feline behavior literature into a practical framework you can actually use at home. We’ll break down the five core environmental systems (physical, nutritional, social, elimination, behavioral) and map them to real-world design choices, including where modern smart devices genuinely help—and where they’re just expensive distractions.

1. Why Indoor Cats Need More Than “Safety”

Most major veterinary bodies now tell owners to keep cats indoors or in protected outdoor spaces. Lifespan data backs that up: indoor cats live significantly longer than free-roaming cats and face fewer risks from trauma, infectious disease, and wildlife.

The problem: a growing body of research shows that an indoor life without adequate enrichment can create a different set of welfare problems:

- Boredom and obesity are described as “very common” in indoor cats and linked to medical and behavioral issues.

- A 2019 systematic review concluded that the impact of an indoor lifestyle on feline welfare is under-recognized and that many behavior disorders stem from environmental deficits.

- AVMA notes that indoor cats without sufficient enrichment may develop distress, defined as an inability to cope, which can manifest as aggression, inappropriate urination, overgrooming, or withdrawal.

In other words:

“Safe but boring” is not an upgrade—it’s just a different kind of problem.

The answer is environmental enrichment: deliberately designing the cat’s living space and routines so they can express natural behaviors—hunt, climb, hide, explore, scratch, and rest—without being exposed to outdoor dangers.

2. Scientific Frameworks: Five Systems and Five Pillars

Two frameworks show up again and again in the literature:

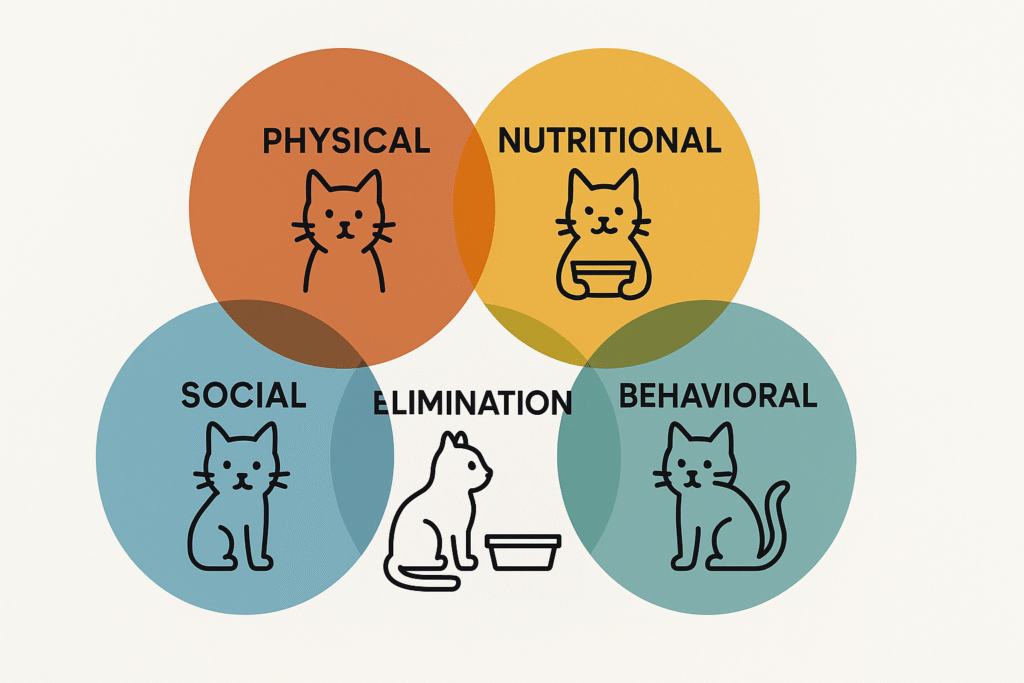

2.1 The Five Environmental Systems

Herron & Buffington’s work on indoor cat environments organizes the cat’s world into five systems:

- Physical – space, structures, hiding places, vertical territory

- Nutritional – how and where food is delivered, not just what is fed

- Social – interactions with humans and other animals

- Elimination – litter boxes, location, cleanliness, substrate

- Behavioral – opportunities for play, predation, exploration, and choice

Weakness in any system can contribute to stress and disease. Behavior consultations often start by walking through each system and asking: “Where is this cat’s environment failing them?”

2.2 The Five Pillars of a Healthy Feline Environment

The AAFP/ISFM Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines and related resources describe five “pillars” indoor cats need:

- Safe places (hiding spots, elevated vantage points)

- Multiple and separated key resources (food, water, litter, scratching, resting areas)

- Opportunity for play and predatory behavior

- Positive, predictable human–cat interaction

- An environment that respects the cat’s sense of smell

Viewed together, these frameworks give you a blueprint:

A good indoor home isn’t just four walls—it’s a system that meets physical, emotional, and behavioral needs at the same time.

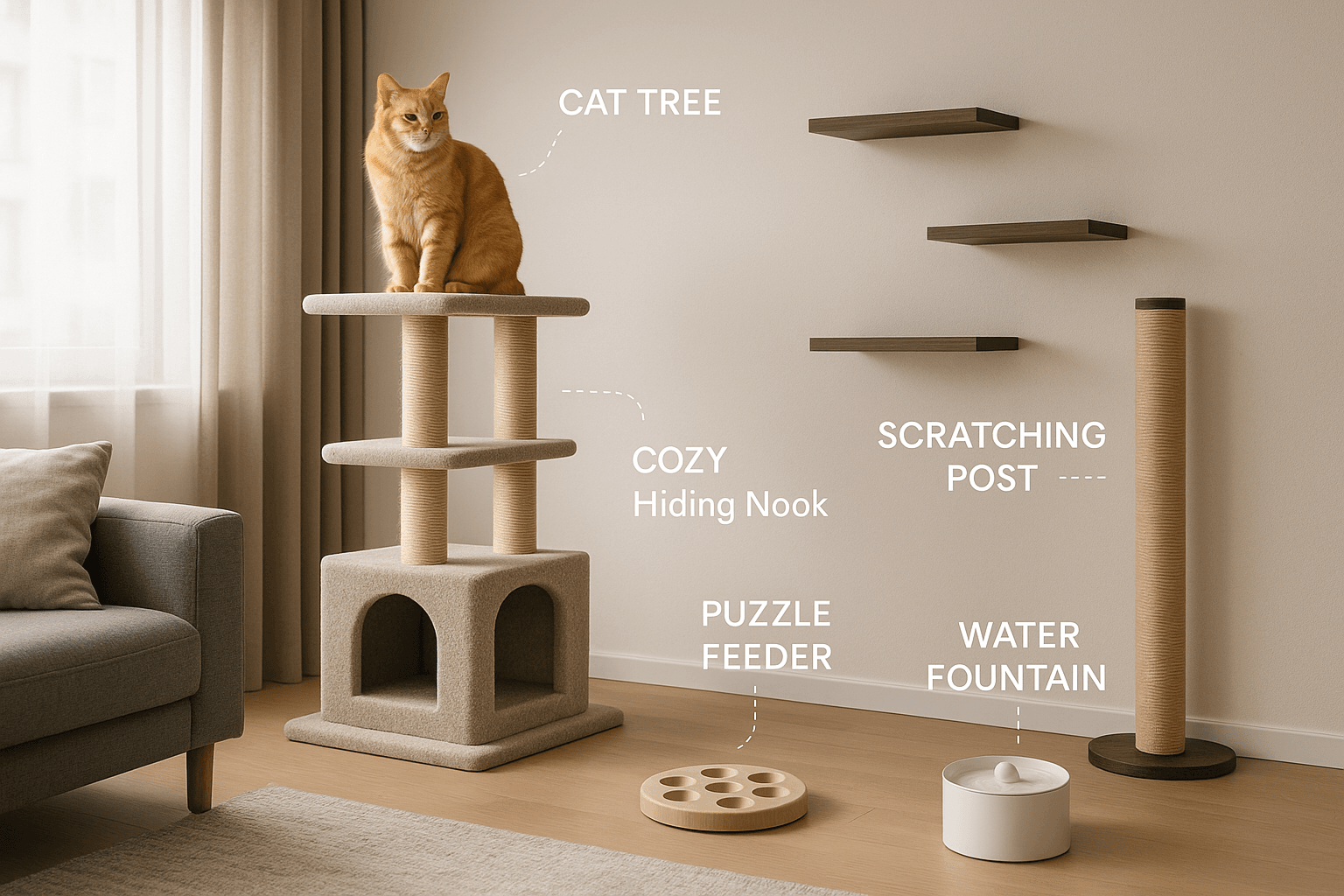

3. The Physical System: Space, Verticality, and Safety

3.1 What Goes Wrong

Common failures in the physical environment:

- No vertical space (no shelves, no cat trees, nothing to climb)

- No hiding places that feel safe and quiet

- Overstimulating layouts (busy windows with constant noise, no retreat zones)

- “Dead” rooms with nothing interesting to explore

Multiple clinical guidelines emphasize that vertical space and safe hiding spots directly reduce stress.

3.2 Design Principles

Evidence-based adjustments that improve the physical system:

- Vertical territory: cat trees, sturdy shelves, or cleared tops of furniture at different heights (low perches for seniors, higher for confident cats).

- Hiding spots: boxes, covered beds, carriers left open, quiet corners—with at least one safe resting/hiding area for each cat in each key room.

- Scratch zones: vertical and horizontal scratching options, placed where the cat actually wants to be (near human spaces, doors, transitions), not banished to a hallway.

Smart devices here play a supporting role at best (e.g., cameras to check how spaces are actually used), but they do not replace the need for physical structures.

4. The Nutritional System: How You Feed Matters as Much as What You Feed

4.1 Free-Feeding and Obesity

Static bowls filled all day are convenient—but they remove one of the cat’s most important jobs: working for food. Many sources highlight that boredom and obesity are tightly linked, and that feeding style is a major driver of both.

4.2 Enrichment Through Feeding

VCA and other veterinary resources emphasize using food puzzles, foraging, and varied delivery to add both physical and mental exercise:

- Puzzle feeders and slow feeders

- Scatter feeding/hiding small amounts of kibble in safe spots

- Rotating locations of bowls or puzzles (while keeping litter and water predictable)

Smart feeders can help with:

- Portion control and schedule consistency (useful for weight management)

- Night feeds without disturbing humans

- Data on portions and compliance

But:

A smart feeder that always drops food in the same bowl, in the same spot, with no puzzle aspect is not enrichment. It’s just automation.

The highest-impact approach is often a hybrid: a smart feeder controlling total intake plus 1–2 daily meals delivered via puzzle or foraging setups.

5. The Social System: Predictability Over Constant Attention

5.1 Social Stress and “Invisible” Problems

Indoor cats face social stressors that outdoor cats can escape:

- Crowded multi-cat homes

- Dogs or children with unrestricted access

- Humans who overschedule cuddles or handle roughly

Behavior literature notes that many aggression, fear, and elimination problems trace back to social and environmental mismatches, not “bad cats.”

5.2 Evidence-Based Social Design

Key principles from guidelines:

- Choice and control: give cats the ability to approach or retreat from humans and other animals.

- Predictable interactions: short, consistent sessions of play, grooming, or petting are better than random bursts of intense attention.

- Separated resources: multiple feeding stations, litter boxes, and resting spots reduce competition and bullying.

Smart cameras and treat-dispensing devices can support remote interaction, but they don’t replace the value of calm, respectful in-person contact that follows the cat’s lead.

6. The Elimination System: Litter Boxes as a Welfare Indicator

Litter boxes are often treated as a housekeeping problem. Clinically, they’re a welfare barometer. The environmental guidelines are consistent:

- Number: at least n+1 boxes for n cats

- Placement: quiet, accessible, away from food/water

- Substrate: fine, unscented clumping litter often preferred

- Cleanliness: scooped daily, fully changed regularly

Failing this system leads to:

- House-soiling

- Urinary tract disease exacerbation

- Stress-related cystitis (feline idiopathic cystitis)

Smart litter boxes help with:

- Objective data on frequency and volume of visits

- Early warning of changes in elimination patterns

- Reducing scooping workload so humans maintain cleanliness standards

But they can worsen welfare if:

- noise or cycles scare the cat

- they’re the only box available and malfunction or misread presence

- humans rely on “smart” features and ignore obvious environmental issues (privacy, access, substrate)

The science is clear: smart boxes are tools, not magic. The underlying litter box system design must still respect feline preferences.

7. The Behavioral System: Play, Predation, and Cognitive Load

7.1 Why Play Is Non-Negotiable

Multiple guidelines and reviews converge on one point: play and predatory behavior are mandatory, not optional, for indoor cats.

Without opportunities to stalk, chase, pounce, and “kill”:

- Energy is redirected into aggression, furniture destruction, or self-injury

- Obesity and muscle loss progress faster

- Anxiety and frustration increase

7.2 Structured vs. Passive Enrichment

Effective enrichment combines:

- Structured sessions – human-led play with wand toys and interactive games, ideally 5–10 minutes once or twice daily.

- Passive enrichment – toys, scratching posts, views, and puzzles available when humans are busy.

Cornell highlights toys as key tools to encourage exercise and problem-solving while strengthening the human–cat bond, warning that lack of stimulation can lead to obesity and behavior problems.

Smart toys (motion toys, interactive balls, laser devices) can increase activity, but only if:

- They match the cat’s play style

- Sessions are limited and not overwhelming

- Laser play ends with a “catchable” toy or treat to prevent frustration, as many behavior resources recommend.

8. Measuring Welfare: How Do You Know It’s Working?

Most owners underestimate their cat’s stress level. Research and guidelines suggest watching for:

Positive indicators:

- Regular play and exploration

- Normal appetite and grooming

- Relaxed resting postures in multiple locations

- Social interactions initiated by the cat

Warning signs:

- Hiding most of the day

- Sudden changes in litter box use

- Overgrooming, bald patches

- Aggression toward humans or other pets

- Hypervigilance (startles easily, constantly on edge)

If these appear, the literature is clear: you don’t just “discipline” the cat—you re-evaluate the environment across the five systems and, if needed, consult a veterinarian or veterinary behaviorist.

Smart devices with logging (litter metrics, feeder logs, activity trackers) can help identify trends—sudden drops in activity, changes in elimination frequency—but interpretation still requires clinical judgment.

9. Where Smart Pet Tech Helps—and Where It Doesn’t

From a scientific standpoint, smart devices are environmental modifiers, not core needs. The question is not “Do you have gadgets?” but:

“Does this device help your cat express natural behavior or reduce stress in a measurable way?”

9.1 Clear Wins

Based on current guidelines and common clinical scenarios, tech clearly helps when it:

- Makes it easier to keep resources clean and consistent (smart feeders, automated litter scooping, fountain flow reminders)

- Provides objective data that can be shared with vets (feeding logs, litter visit frequency, activity trends)

- Supplements, not replaces, interactive play (e.g., motion toys that run during work hours plus wand sessions at night)

9.2 Neutral or Risky Uses

Tech is neutral—or harmful—when it:

- Adds noise and movement with no escape or choice

- Overcomplicates basic needs (e.g., complex feeders that malfunction, leaving no backup food)

- Encourages owners to ignore behavior changes because “the app says everything is fine”

The literature warns that environmental complexity must still be controllable and predictable from the cat’s perspective. More devices do not automatically mean better welfare.

For a site like PetTech AI, the responsible framing is:

- Smart devices are tools to support the five systems and five pillars,

- not a shortcut to “enrichment without effort.”

10. Implementation Roadmap: A 30-Day Enrichment Plan

To translate the science into action, here’s a realistic plan for a typical one- or two-cat indoor home.

Week 1 – Audit and Fix the Basics

- Map food, water, litter, scratching, resting, and play areas.

- Add at least one safe hiding place and one vertical perch in each main living area.

- Check litter box number, size, and location (n+1 rule; quiet, accessible).

Week 2 – Upgrade Feeding and Play

- Convert one meal per day into puzzle or foraging form.

- Start two 5–10 minute wand-play sessions per day, ideally before meals.

- Introduce a small rotation of toys; put some away and reintroduce weekly.

Week 3 – Add Smart Tools Strategically

- If using a smart feeder: program consistent schedules and portions, but keep at least one meal “earned” via play or puzzle.

- If considering a smart litter box: keep at least one standard box available while the cat acclimates; monitor usage closely.

- Use cameras or basic trackers to observe what your cat actually does when you’re away—then adjust the environment accordingly.

Week 4 – Fine-Tune Social and Sensory Environment

- Establish predictable daily “contact windows” for petting, grooming, and play—always letting the cat decide how long.

- Reduce loud, unpredictable stimuli in key cat areas; provide scent stability (avoid heavy room deodorizers; use familiar bedding).

- Watch for subtle improvements: more relaxed resting, voluntary play, less hiding, fewer minor conflicts.

If problems persist—especially elimination issues, aggression, or self-harm—guidelines are unequivocal: involve a veterinarian or veterinary behaviorist.

References

- Cornell Feline Health Center. Safe Toys and Gifts. Encouraging exercise and cognitive enrichment while preventing toy-related injuries.

- Herron ME, Buffington CAT. Environmental Enrichment for Indoor Cats. Compendium and related follow-up on environmental systems (physical, nutritional, social, elimination, behavioral).

- Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery / AAFP–ISFM. Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines and position statements on enrichment and life stages.

- AVMA. Indoor cats: wellbeing requires more than physical safety. Discussion of distress, enrichment, and behavior problems in indoor cats.

- VCA Animal Hospitals. Enrichment for Indoor Cats and Enriching Your Pet’s Environment with Their Food. Practical recommendations on play, feeding style, and stress reduction.

- VeterinaryPartner / VIN. Feline Enrichment: Meeting the Essential Needs of Cats. Overview of enrichment’s role in preventing behavior and health issues.

- MSPCA, AAHA, and other veterinary resources on vertical space, hiding areas, and practical indoor enrichment strategies.

- Foreman-Worsley R, Farnworth J. A systematic review of social and environmental factors and their implications for indoor cat welfare. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 2019.

Disclaimer

The information in this whitepaper is provided for educational purposes only and does not replace professional veterinary advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult your veterinarian or a qualified veterinary behaviorist before making major changes to your cat’s environment, diet, or activity level—especially if your cat has existing medical or behavioral issues.

PetTech AI participates in affiliate programs, including Amazon Associates and other partner networks. We may earn a commission when you purchase products through links on our site, at no additional cost to you. Our content and evaluations are based on independent research and expert sources, not paid placement.